IELTS! image taken from en.wikipedia.org via google search for images licensed for commercial reuse with modification

There are a number of us teaching IELTS afternoon classes at the ELTC this term, so I thought it would be a good idea for us to share ideas to use in IELTS classes. With the help of the TD team at the ELTC, this was duly organised and took place on Wednesday 11th October. I kicked off by sharing a couple of my go-to activities and then everybody else followed suit.

I also promised to provide a written record of the workshop, for everybody to use as reference. Therefore, this post is a write-up of all the ideas that emerged, both for my colleagues to refer back to and for anyone else out there blessed with IELTS classes to dip into, divided up by skill to make it more user friendly.

Writing

1.

I’ll start with mine! Nothing spectacular but it worked well with my group…

Aim:

To encourage students to look at their feedback carefully rather than burying it in their bags never to be seen again. To create the need for students to ask when they don’t understand an element of the feedback (rather than ignoring it), hopefully rendering future feedback, presented similarly, more useful.

Procedure:

After writing feedback on a set of Part 1 or Part 2s, as part of the marking process, T makes a checklist based on common errors the students have made. Save this for later.

In class, group students in 3s or 4s, hand out the pieces of writing and have them look at their feedback. They should use the feedback to make a group checklist of things to remember next time they do a similar piece of writing. (To do this successfully, they need to understand their feedback. T monitors and provides further explanation when needed.) When students have finished, regroup them so that each new group contains one student from each of the previous groups. They should compare their checklists and add any extra items. T hands out the pre-prepared checklist for students to compare with their own (or in my case, as marking time was short and I hadn’t quite got round to typing up the checklist, I put it on Google classroom the next morning for the students to access at home!).

2.

Aim:

Familiarise students with the writing marking criteria and help them become better aware of their strengths and weaknesses in relation to these.

Procedure:

Give students a handout with some sample feedback comments together with the marking criteria headings (see example below). In groups, students look at the sample comments and decide together which of the criteria they affect.

They can then look at a piece of writing you have given them feedback on and categorise your comments in a similar way. In doing this, they can see which criteria they have most/least positive/negative feedback within and thereby see where their strengths and weaknesses lie.

3.

Aim:

Encourage students to focus on paragraph construction/organisation.

Procedure:

Put students in groups and give them a part 2 question to brainstorm ideas for. Give each person in the group a topic sentence for a possible paragraph for that essay question. They add the next sentence and pass it on. This continues for a few sentences until the paragraph is complete. In order to add their sentence, the students have to read the paragraph carefully and understand where it is going. They will also have to look at the language used carefully, in order to use rich lexical chains rather than repeating a particular word over and over across sentences.

Once the activity is finished, stick the paragraphs up around the room then get students to walk round in pairs to look at and analyse them. (You can give them/elicit a checklist of things to look for). On the basis of this, they decide which paragraph is best and why. You could then ask them to look at a paragraph of their own from a previously marked piece of writing and analyse it in a similar fashion.

4.

Aim:

Get students using chart/graph language for part 1 and give students practice in understanding what is happening in such visuals.

Procedure:

Students draw a chart or graph but don’t label it. T redistributes the charts so that each student has another student’s chart or graph. They they then have to analyse it, decide what is going on and create the labels. The charts/graphs are redistributed again and this time students have to pick out 3 features and write about them in part 1 fashion. Once finished, the charts/graphs and accompanying paragraphs can be stuck on the wall for students to walk round, analyse (elicit what criteria they should use first, of course) and rank.

Speaking

For speaking, I brought along a print out of my Part 2 Speaking Game , which aims to encourage students to speak for a full two minutes, and my colleagues brought the following:

1.

Aim:

Develop fluency and use of vocabulary (using the game “Just a minute”)

Procedure:

Give the students this handout/similar to familiarise students with the game and elicit the rules:

Once they have understood the goal and rules, brainstorm a list of IELTS-style topics. The students then use these to play “Just a minute”. The repetition factor applies only to content words/ideas.

Variation:

Rather than having students interrupt the speaker for the repetition/hesitation, the speaker is encouraged to speak for a minute uninterrupted and, at the end of the game, the other two students in the group score him/her based on how much/little repetition/hesitation there was.

2.

Aim:

Work on expanding responses to IELTS speaking questions

Procedure:

Brainstorm and write on the board as many IELTS topics as your class can think of between them. Students then mingle, find a partner and ask that partner a question about one of the topics on the board. The response should be well-developed but the student who asked the question should also ask follow-up questions to encourage further expansion. Before they start, tell students that they will have to report back a few interesting things they find out, to encourage them to listen carefully too. You might also like to model expansion, to give students a clear target. T monitors and does delayed feedback on the end, commenting on expansion, use of vocabulary etc not just grammatical errors.

3.

Aim:

Develop fluency in speaking

Procedure:

Prepare sets of cards, with one IELTS speaking topic per card. Students pick a card and have to speak about the topic for a minute. Then next time, they have to speak for a minute and a half. Then two minutes. This helps them to build up the length of time they can speak for. The topics can be broad e.g. “holidays” or you can make it harder by making the topic more specific or restricting the time frame.

4.

Aim:

Work on planning/preparation for speaking part 2

Procedure:

For homework, students choose an image that relates in some way to whichever topic you have been looking at in class. They should also prepare some notes that will help them speak about that image. Restrict the size of the paper they can use, to something of the size that they will get for an IELTS part 2 speaking exam task. In class, everybody uploads their pictures to Google classroom, in order to project them for everybody to see, and then students take it in turns to stand up at the front of the class, and use their notes to speak about the image.

I then made the suggestion that students organise their speaking part 2 note paper as follows:

The idea is that in the pressure of the moment, when they glance down at their notes while speaking, it will be easier for them to keep track of whether they have spoken about all the required elements. Credit to my ex-DOS Jonny Ingham, an IELTS speaking examiner, from whom I got this idea while teaching IELTS at IHPA! He said the students who use the note-making time effectively always out-perform those who don’t, as the response tends to be better organised and clearer.)

Reading/Listening/Vocabulary

1.

Aim:

Develop the skill of matching paragraphs to headings.

Procedure:

Give each pair of students one paragraph between 2 from an IELTS reading text. (Depending on how big your class is and how many paragraphs the text has, you may have more than one pair with the same paragraph. This doesn’t matter.) Students look at their paragraph, discuss it together, and write down a few key words that sum it up. Only once they have done this do you then distribute a list of the headings, one of which belongs to their paragraph. Using their key words, and looking again at their paragraph, they decide which heading is theirs. They must agree and be able to prove their answer to the class i.e. be able to explain how the heading corresponds with the content/vocabulary of their paragraph.

Variation:

Instead of giving students a paragraph, give out just the topic sentences of each of the paragraphs and the list of headings. Again, they must work together and decide which heading goes with the topic sentence they have by noticing how the words in the topic sentence correspond (positively or negatively) to the words in the headings.

2.

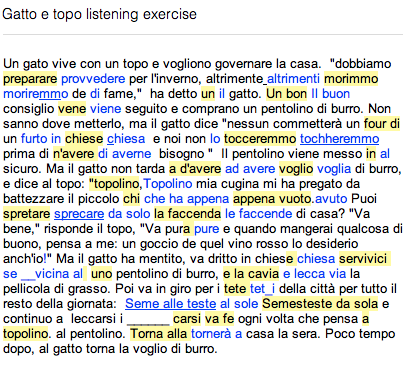

Aim:

Encourage students to identify the wrong answers in a reading or listening, as a way to help them identify the right answer.

Procedure:

Students work together to look at a multiple choice question/it’s possible answers and see which wrong answers they can identify by using the text. “It can’t be c) because it says x while in the text it says y” With listening, this can be done whole class by (re)playing short sections of text in order for students to focus on one question at a time.

Variation: Before playing a listening text, have students look at the questions/possible answers and have them discuss what they would expect to hear if each of the choices were the correct answer. They should think about different ways of expressing the answers.

3.

Aim:

Expand students’ vocabulary

Procedure:

Every time you use a text in class, follow up reading skills work by getting students to call out any words they found difficult and boarding them. They then need to do some word work – find synonyms and opposites, word families, useful expressions etc. Get them to keep a notebook where they can group vocabulary by topic.

Variation:

After looking at a text, tell students that they need to know all the vocabulary in it as you will test them on a random selection of words from it in the next lesson. If they don’t know any words in it, they will need to go away, find out what the words mean and learn them.

4.

Aim:

Develop students’ awareness of collocation

Procedure:

Before a listening lesson, look at the transcript of the listening text and pick out up to eight good collocations (you don’t want to overdo it!). After students have done the listening exercises that go with the text, dictate the first half of each collocation for students to write down. Play the listening again and students should listen in order to write down the second half of each collocation. Once they have got them all, get students to use the collocations by making sentences/asking and answering questions etc. Draw attention to any cases where they should be avoided in writing (e.g. if they are too informal).

Resource recommendations

Two particular books were mentioned as go-to books:

1.

IELTS Resource Pack

Has lots of useful speaking (also a good resource simply of [almost] endless speaking topics if you are at a loss) and lots writing activities that encourage interaction.

I would have mentioned it if one of my colleagues hadn’t. One of my favourite activities involves students looking at two part 2 essays, both of which contain a mixture of good and bad sentences, and identifying which are the good so that they finish with one good part 2 essay. There are also some good part 1 writing activities.

2.

IELTS Testbuilder

This has good explanations for reading texts regarding why certain answers are wrong, why the correct answers are correct etc.

Final tips…

1.

With the map questions in listening, take advantage of the box sizes – a big square won’t be a little cafe, a tiny square won’t be a shopping centre etc.

2.

Don’t forget task repetition: using speed dating/speaking ladders can facilitate task repetition within speaking activities, which will have a positive effect on fluency and complexity.

3.

I will cheekily add: Don’t forget my Useful links for IELTS post for a wealth of IELTS-related links, and my Top 10 resources for teaching IELTS might be of interest too.

I hope this post is useful to some of you. Do any of you have any go-to activities or resources for IELTS? If yes, please do share them by using the comments box below this post. 🙂

(To my colleagues: if I have missed anything or got anything wrong, please let me know and I’ll make changes accordingly. Scribbling things down and then subsequently trying to decipher them may not be the most reliable method but it was all I had!)