On 29th November 2023, I attended a webinar, “Supporting autistic students”, run by NATESOL and delivered by Carly Miller, who is a disability coordinator at Leeds University. This post will use the slides she so kindly provided to summarise the session and reflect on what she said, relating it to my own experience and practice.

These were the aims and objectives:

Carly started with defining the social and the medical models of disability:

In the medical model, the disability itself is the barrier, while in the social model it is the environment and society that create the barriers. Of course the session being delivered by Carly ascribes to the social model given that it is to raise awareness of autism and how to make there be fewer barriers for autistic students.

Next was the definition of autism:

Here is a very helpful explanation of how the autism spectrum works, explaining that it is not linear (and nowadays labels such as “high-functioning” and “low-functioning” are increasingly being moved away from) and illustrating how someone with autism usually has a spiky profile in terms of challenges and strengths. There is thought to be a genetic component but not a straightforward “this gene makes this happen” one. There is no cure. Going back to the disability models, in particular the social model of disability, many problems experienced by autistic people arise from trying to operate in a neurotypical world with a brain that perceives things differently from neurotypical brains. Hence this session.

Next Carly explained the diagnosis process in England:

As is clear from the above, it is difficult to get a diagnosis. Carly told us that she has been on the waiting list since she got on to it after the pandemic, having noticed during the pandemic various aspects that made her suspect she was autistic. As with everything NHS-related, it takes a long time. For example, I saw my GP on the 7th November and got referred to be assessed, but at the time of writing have yet to know whether I have been accepted on to the waiting list! Fortunately, at the university, despite not having a diagnosis yet, I have been able to request and get a reasonable adjustment in place to alleviate my sensory sensitivities (one of the possible elements of autism). Carly also suggested that depression, anxiety and/or trauma are frequent consequences of being autistic and may lead to it being diagnosed but that they are not autism, they are just the result of the way in which autistic individuals must operate in a neuronormative world, in which we are viewed through a medicalising lens:

So…what is autism then? Here is Carly’s summary of it:

Autism is a type of neurology/neurological system. Autistic brains take in more information and they process it differently, resulting in different output. Different rather than worse/broken/disordered. Diagnostically, however, the criteria are framed as deficits/viewed negatively and that is linked to the historical evolution of autism and autistic brains as a concept. (Asperger and Kanner are the earliest people to have worked on it scientifically, and at the time Eugenics was very dominant…). According to Carly, approximately 1 in 100 people are diagnosed as autistic but that is potentially a huge underestimate. (Somewhat unsurprisingly given the barriers to getting diagnosed.) Part of the underestimate relates to what she discussed next – autism and females:

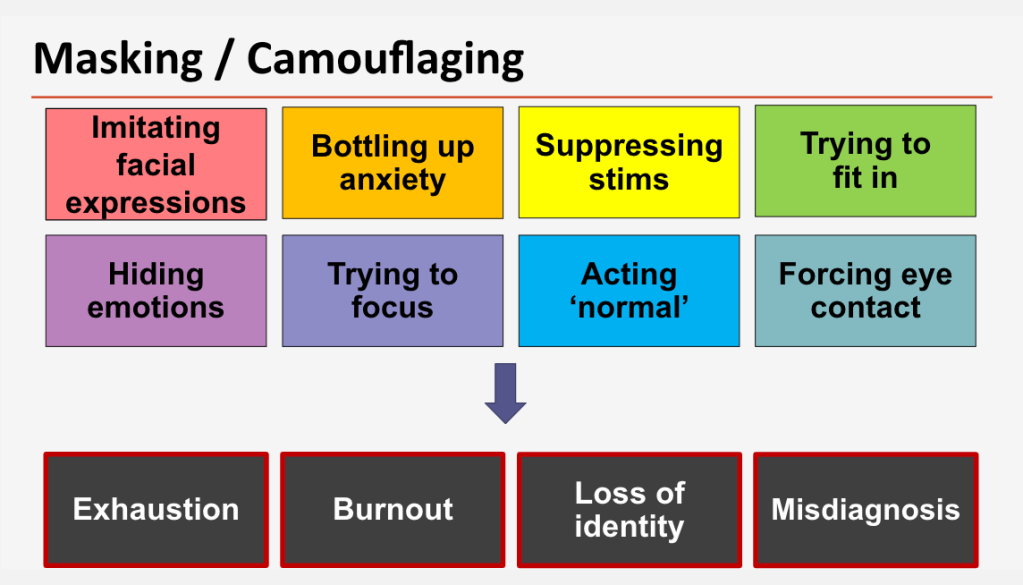

The stereotypical autistic person is a white, cis-het young male. (I believe this is at least partly due to the early work published by Asperger and Kanner focusing on boys – at the time, girls were more likely to be dismissed as “feeble-minded” and institutionalised for being different – though they did also work with girls, and diagnostic criteria developing accordingly.) However, there is no ‘female autism’. Rather, the spectrum of traits associated with autism is broad and autistic peoples’ ability to mask is also varied, regardless of their gender. Of course, masking also contributes to diagnostic barriers. For example, if the person doing the diagnosing observes an autistic person making eye contact during the diagnosis, that might count against them being diagnosed when in fact they have learned to make eye contact in order to be acceptable, and carry it out with discomfort. Carly summarises thus:

(For anybody who isn’t aware, “stims” are usually repetitive movements which autistic people do either because it feels good or as a coping mechanism when overstimulated. The stereotypical one is rocking backwards and forwards but autistic people often find ways to stim that are less noticeable when around people e.g. tapping a foot, twiddling hair, fidgeting with an object.) Eye contact is an important one to think about in the context of teaching. We are taught that eye contact and sitting still shows that someone is paying attention. For an autistic person it more likely means they are working hard on doing the eye contact thing and sitting still, but therefore have less brain available to actually take in what is being said/the content of the lesson. So as teachers we need to accept that traditional images of what good learning looks likes do not apply across the board. This is an example that leads nicely into what Carly talked about next:

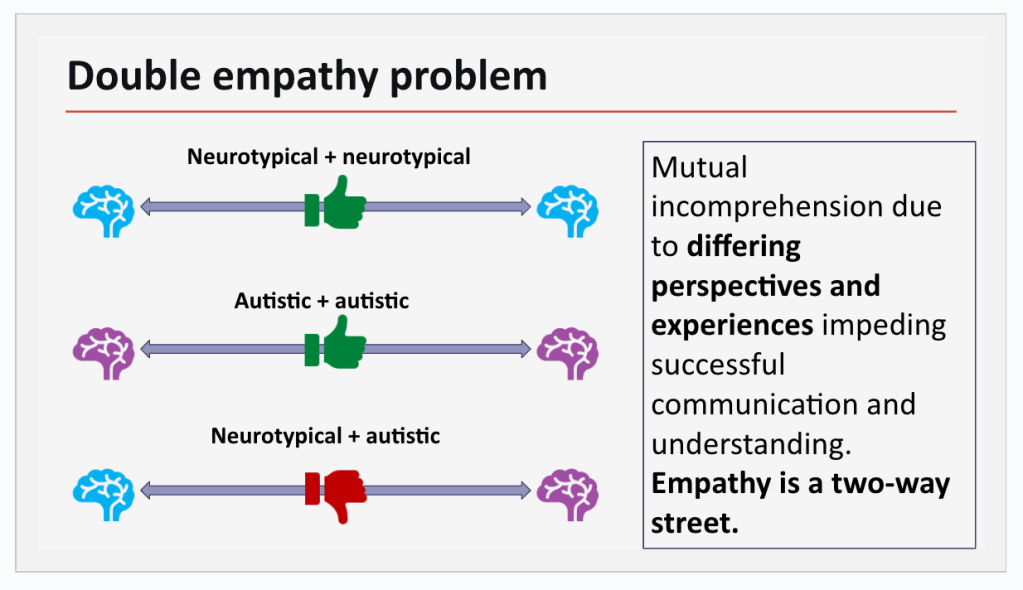

What this slide illustrates is that generally, when a neurotypical person is talking with another neurotypical person, and when an autistic person is talking with another autistic person, communication is generally successful. However, when a neurotypical person and an autistic person communicate, there is a much higher chance for communication issues/breakdown/misunderstandings. (Diagnostically, this is framed as an autistic deficit, of course!)

A personal example of things going wrong that fits nicely here: We were unpacking the car and I was holding the keys and a bunch of other stuff that had been in the car. My wife asked me to put everything inside. So I did. Came back out, we got some more stuff and she asked me where the keys were, in order to lock the car. They were inside, in the place where the keys go! Taking things literally is common in autistic people. (I now know that “everything” doesn’t apply to keys in this situation!) A teaching example that also fits nicely: I always did a brief meditation at the start of class with my students, setting it up as a routine at the start of the course. On one occasion, the second time I did with a particular group of students, after the “and then when you are ready, you can open your eyes” at the end, one student sat with their eyes closed for markedly longer than everyone else. “You said ‘when you are ready'” they said afterwards. Fair!

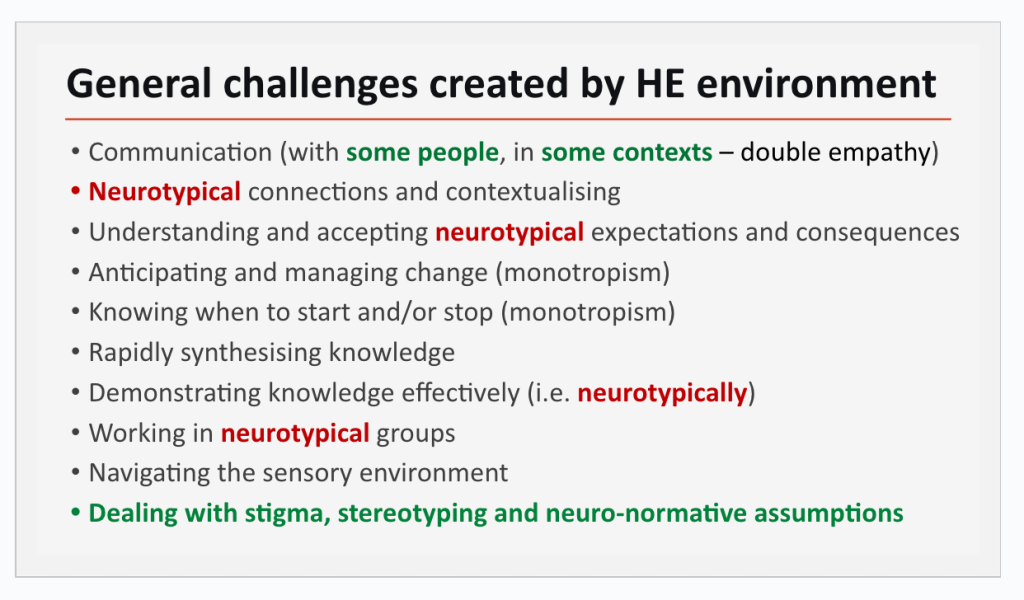

So, speaking of teaching, Carly next moved on to talking about what issues might arise in the higher education environment (NB much of it is applicable to any other teaching environment!):

It’s not first on the list but I am going to lead with “navigating the sensory environment” as that is something that neurotypical people do not typically perceive as a potential issue. Autistic people often are hypersensitive, hyposensitive or a combination of the two to their environment/what is happening. So, hypersensitive is when you are overstimulated by elements of the environment e.g. light (fluorescent lights in particular!), sound, smells, temperature and hyposensitive means experience low levels of sensory feedback. For example, I attended a work training day that took place in a room with lots of fluorescent strip lights and with lots of people who at times were all talking simultaneously (group work!) and at lunchtime instead of attending the lunch provided, I crept off to an empty classroom with the lights off and waited for it to stop hurting. (Spoiler: it didn’t fully stop hurting until the following afternoon!) In our classrooms, I usually switch some of the lighting off so that it is less overwhelming (fortunately most of the rooms enjoy a lot of natural light so it doesn’t mean we are sitting in semi-darkness! Obviously in winter this is trickier…).

Anyway, Carly focused on the common issues as follows:

Starting with processing:

If you are neurotypical, for “interference from sensory stimulation”, imagine you were trying to be a student in a language lesson that was taking place in a night club (ugh) or in a supermarket (ugh) at busy time. Imagine how it would feel trying to concentrate on what you were being taught and asked to do. How long might it take you to complete a task? For a student in your classroom, as well as hearing you, they hear (at the same volume) whatever is going on outside an open window/door, the air system, the lighting (yes lights are loud!), the noise of other people existing in the same space, possibly whispering, typing etc. So focusing on what you are saying/asking them to do is hard work! So how can we help? According to Carly:

What do we notice about this? Yup, it’s general good practice for the most part! But this is even more important for autistic learners and also any learners who are neurodivergent in whatever way. I would add: consider that the classroom doesn’t actually *need* to be maximally bright… Also, let students wear noise-cancelling earphones for individual tasks if they want to. And remember silence can be golden – as in, don’t be afraid of it! Pause for longer between instructions, allow longer thinking pauses before eliciting ideas. At the start of a task, give students a chance to get started before deciding they weren’t listening and approaching them. Also, don’t hint at what you want them to do because they probably won’t do it and it won’t be because they are being bloody minded!

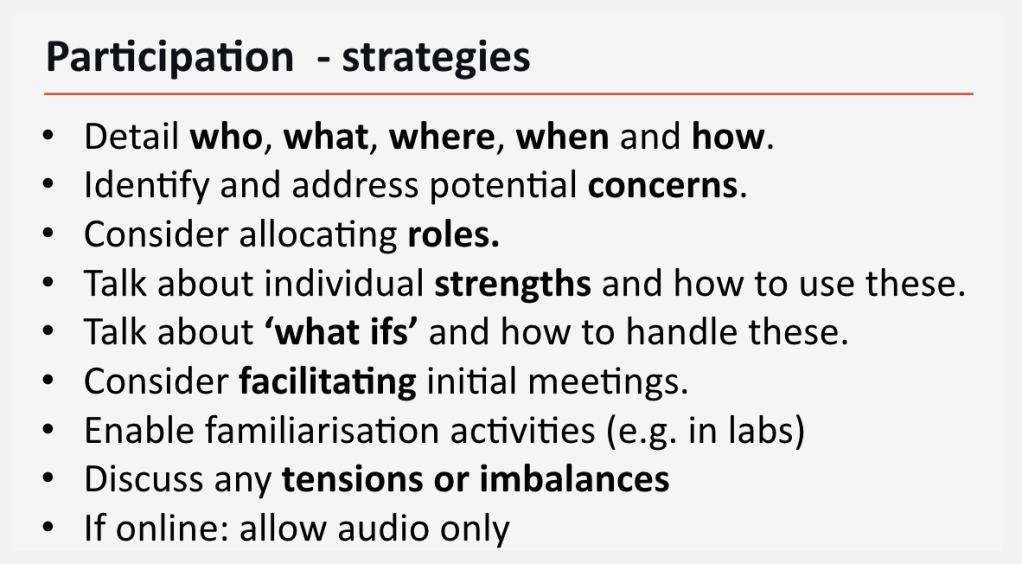

Group work can be very hard work for autistic students. (If we think back to the double empathy thing) For starters, at school, you were probably the kid who nobody wanted to work in a group with because you were ‘weird’. You have to achieve a task, but you also have to figure out how to contribute while dealing with the noise of all the voices in the surrounding groups. Figure out when is the right time to try and say something without being rude e.g. for interrupting. Process what your group-mates are saying and be able to respond/contribute before they have moved on to another part of the task. All of which is compounded if the purpose of the task isn’t clear in the first place! These are Carly’s suggestions for addressing the issues:

So obviously task set-up is important. I think that is something that could also be helped by consistency – having a routine around how tasks are set up, started and brought to an end so that students know what to expect and what’s going to happen. Being clear with timings could also be helpful. Maybe at the start of a course, explicitly talking about group work and how to do it effectively. Maybe at the start of group work tasks, reminding students to find out what everybody in the group thinks about each element/idea/question/answer before moving on to the next.

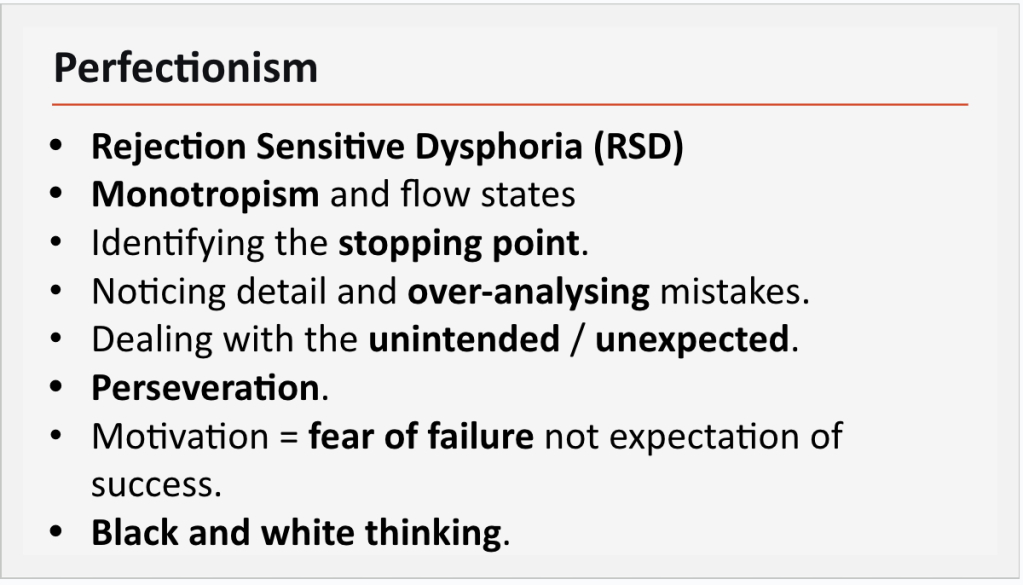

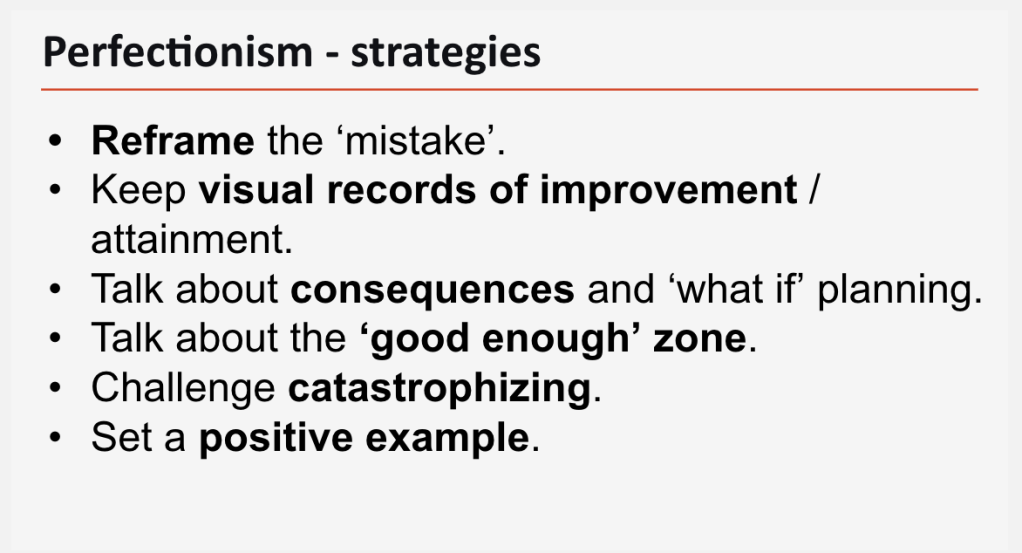

Have you heard the saying “the perfect Ph.D is the finished Ph.D”? I imagine you can see from the above list that these students are likely to be the ones who don’t submit an assessment draft because it’s not finished/perfect enough, or who spend all the time on one part of the task (and do it really well!) but then don’t manage to finish the rest. The ones who worry a LOT about Everything. The ones who struggle when something unexpected happens and disrupts the usual way of things. Here are Carly’s suggestions:

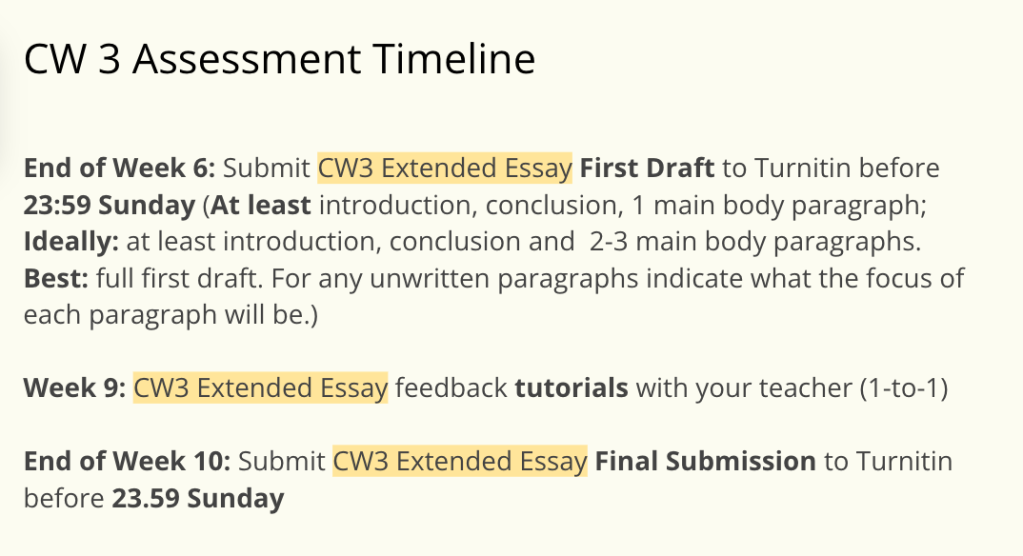

I think an example of this from my teaching last year would be at the first draft of a 2500 word coursework essay stage. Students submit a “first draft” and get feedback on it, which should help them improve before the final submission. This time, because I had pre-masters students and they are notorious for being completely overloaded with assessments, I was very explicit, in multiple lessons and end-of-week emails, about my expectations for first draft submissions:

All students submitted a first draft (result!), drafts were widely varying degrees of complete (from the “at least” to the “best”). They all had at least an introduction, a conclusion and one body paragraph. The “at least” requirement was doable, even with all the drains on their time. It also hopefully helped all of the students who would otherwise have potentially submitted nothing rather than submitting something incomplete. I also did explain why “best” was best (maximum feedback potential) but that “at least” is also good/a success, not a failure, and so much better than nothing. Also, emphasising that “if you don’t submit anything, I can’t give you any feedback help you improve it” (I guess this is clarifying consequences and dealing with “what if I haven’t finished” type thoughts!). Anyway, back to the session:

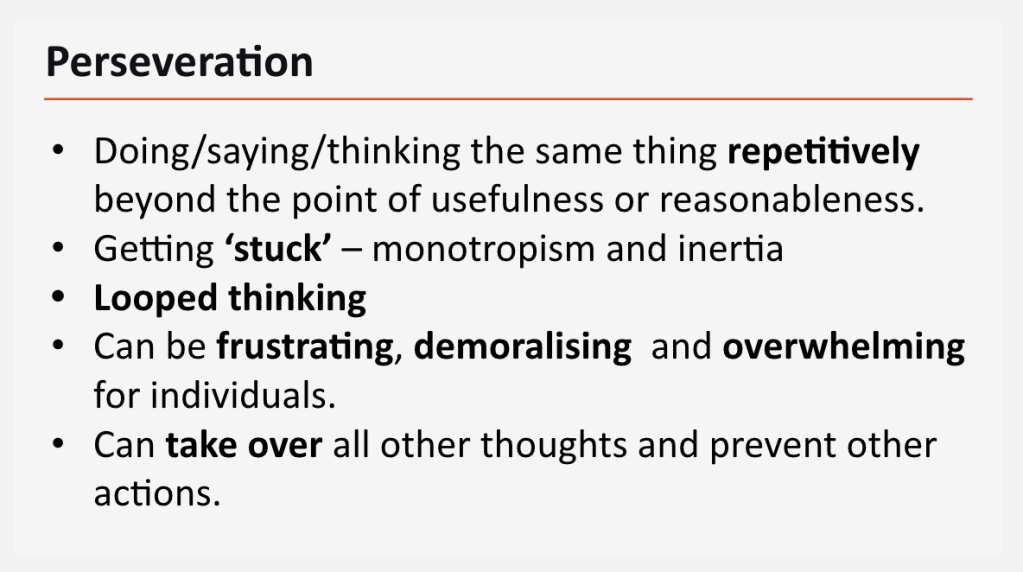

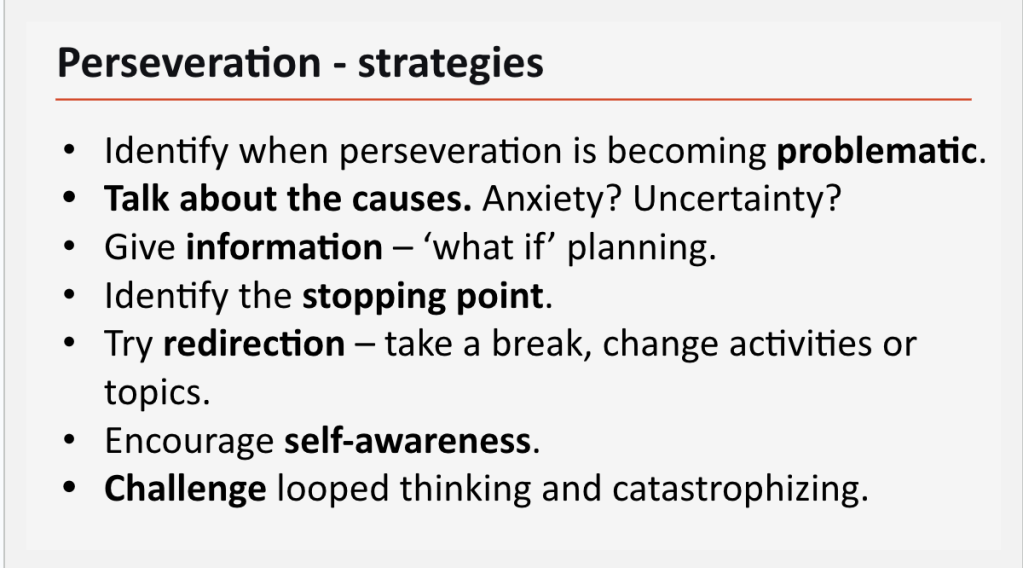

Here is a good explanation of monotropism. (Note: it can also be positive!) In terms of challenges, changes of attention/focus (so transitions in lessons, transitions between lessons) can be difficult. Carly offered some strategies for dealing with perseveration when it becomes a problem.

I think it could be helpful, in addition to making sure task timings are clear ahead of the task, during the task (especially for longer tasks) give a good lead-time to the end of the activity. So firstly, making it clear when a task is a short task, a medium task or a longer task. With a short task (5 minutes), saying when two minutes are left, one minute. With a medium task (up to 15 minutes, say) 5 minutes, 2 minutes. With longer tasks, depending on the length, give a warning half way through, 10 minutes before the end, 5 minutes, 2 minutes. So that there is time for the student to take themselves out of that activity and be ready for the next. Depending on the type of task and the desired outcome, where relevant reassure students that it is ok if they haven’t finished by the allocated time. In terms of looped thinking and anxiety, personally I have found mindfulness meditation to be a game changer. This is why I persevere and will continue to persevere in introducing it at the start of a course and doing the short meditation at the start of each lesson thing – I wish someone had introduced me to it when I was a student! I think also it really eases the transition from the previous lesson to the current lesson as brains are all over the place when students come into the room.

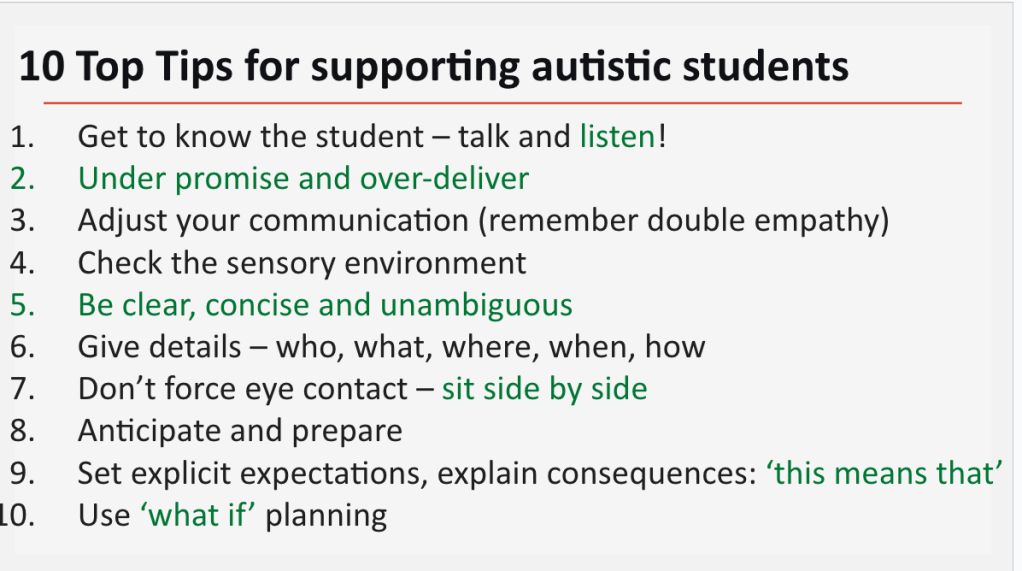

Finally, Carly finished with her 10 top tips for working with autistic students:

I suppose a lot of this comes back to challenging our assumptions about what good learning looks like and what a good learner does and doesn’t do. Maybe when we are planning tasks, think also about how we expect the task to look when being done ‘right’ and then applying the double empathy lens. How else could it look? Is the student who isn’t talking much or who isn’t looking at me actually disengaged? What could we do in the task set-up to enable participation for those who struggle to participate? How might that participation look? What evidence of engagement can I look for outside of habitual ones? What problems might occur? How could we address them? Is there a way to set up the task so that students have more choice about how to participate? And when reflecting on tasks and lessons during and after the event, “are my students learning? how can I tell? how can I find out without viewing them through a neurotypical lens and judging accordingly?”. Then, of course, clarity. Be explicit and don’t assume knowledge! I think possibly also providing opportunities and being supportive, but accepting when students decline those opportunities because they are exhausted/overwhelmed. E.g. building in opportunities to speak, scaffolding/enabling them, but not taking it as a failure if students don’t use it quite as you’d hoped. Maybe having a more flexible framework for mentally evaluating that. Looking at the bigger picture, if you imagine students doing multiple lessons in a day in their various subjects, if we are all demanding speaking and group-work and whatnot, repeatedly, that’s exhausting. I suppose at university, there may be more of a spread of lectures and seminars/practicals, so in some lessons, students can just sit and listen/make notes (which brings other problems for autistic students e.g. around sensory sensitivities), others require more active participation. Maybe within a lesson, don’t assume that they have to be speaking/collaborating to be learning. Quiet tasks are valid too. Maybe all of this also comes back to getting to know your students. Rather than jumping to conclusions, learning about how they learn and what they look like when they are learning/confused/enthusiastic/worried etc.

That brings me to the end of this post (finally, I hear you say!). Here are the links that Carly left us with at the end of the session:

- An overview of the autistic experience

- Guidance on adjustments to vivas for autistic students

- Common sensory issues and potential solutions

- Autism The Positives

Feel free to share your comments of your own experience as an autistic person or from working with autistic students/people.